Fashion is often marketed as glamour, art, and self-expression. But behind the catwalks, glossy storefronts, and endless social media ads lies an industry with devastating consequences. From overflowing landfills to poisoned rivers, from exploited workers to animal cruelty, modern fashion carries a hidden price far greater than the cost on a label. It’s more than style—it’s a global industry with a massive environmental and social footprint. Fashion contributes significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions, consumes more water than nearly any other sector, and produces staggering amounts of waste annually. Its impact is not just in numbers but in polluted waterways, unsafe workplaces, and the suffering of animals entwined in supply chains.

Fast Fashion and the Landfill Crisis

Fast fashion is designed for speed and obsolescence. Retailers churn out cheap, trend-driven clothing in weeks rather than months, pushing consumers toward a cycle of constant buying and discarding.

The result is a waste crisis of staggering proportions. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Landfills received 11.3 million tons of MSW textiles in 2018.” That number has only grown with the explosive rise of ultra-fast fashion brands. Most of these discarded garments are made from synthetic blends like polyester, which take hundreds of years to decompose.

Even before they reach the landfill, synthetic fabrics cause environmental damage. Each wash cycle of polyester clothing releases thousands of tiny fibers into wastewater, which flow through sewage systems into rivers and oceans. These microfibers have now been found everywhere — from the deepest ocean trenches to Arctic snow, and even in human lungs and bloodstreams. The European Environment Agency has warned that textiles are one of the largest sources of microplastics in the environment.

Fast fashion’s waste problem is also a cultural one. Clothes are marketed as disposable, encouraging consumers to treat garments with the same mindset as single-use plastics. A dress might be worn once for a social media post before being discarded. The environmental cost of producing and discarding billions of garments annually is immeasurable — yet entirely preventable.

Fast fashion isn’t free. The environment and the people who make our clothes pay the price.

High-End Brands and Hidden Waste

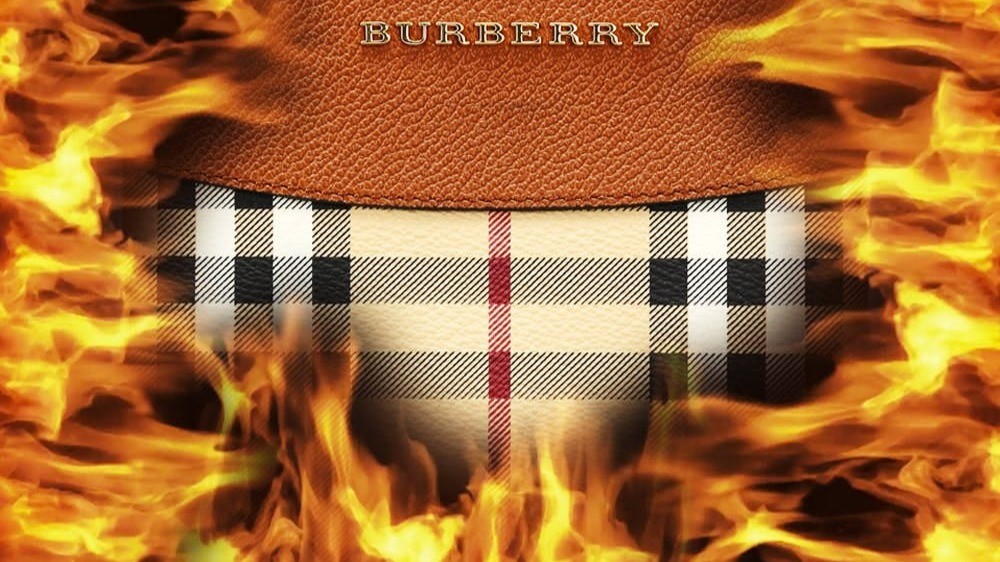

Luxury fashion positions itself as timeless and exclusive, the opposite of fast fashion’s disposability. But the reality is more complicated. High-end brands often manufacture at scale, using the same cost-cutting production methods as their fast-fashion counterparts. And when items don’t sell, they’re not always discounted or recycled — they’re sometimes destroyed.

In 2018, reports revealed that some luxury companies were burning or shredding unsold stock to prevent it from entering discount markets. This practice wastes all the resources — water, energy, labor, and raw materials — that went into producing those garments. Incineration itself releases greenhouse gases and toxins, compounding the harm. Vox reported that brands destroy merchandise “to protect their exclusivity, but at huge environmental cost.”

High-end fashion is also entangled in resource extraction. Cellulosic fabrics like viscose and rayon, made from wood pulp, have been linked to deforestation in Southeast Asia and South America. Meanwhile, luxury leathers and exotic skins are tied to habitat destruction, biodiversity loss, and animal suffering.

Even if a $5,000 handbag lasts longer than a $20 polyester dress, its environmental and ethical costs can be far higher. The sheen of exclusivity often conceals supply chains rife with exploitation and destruction.

The future of fashion is not about making more—it’s about making better.

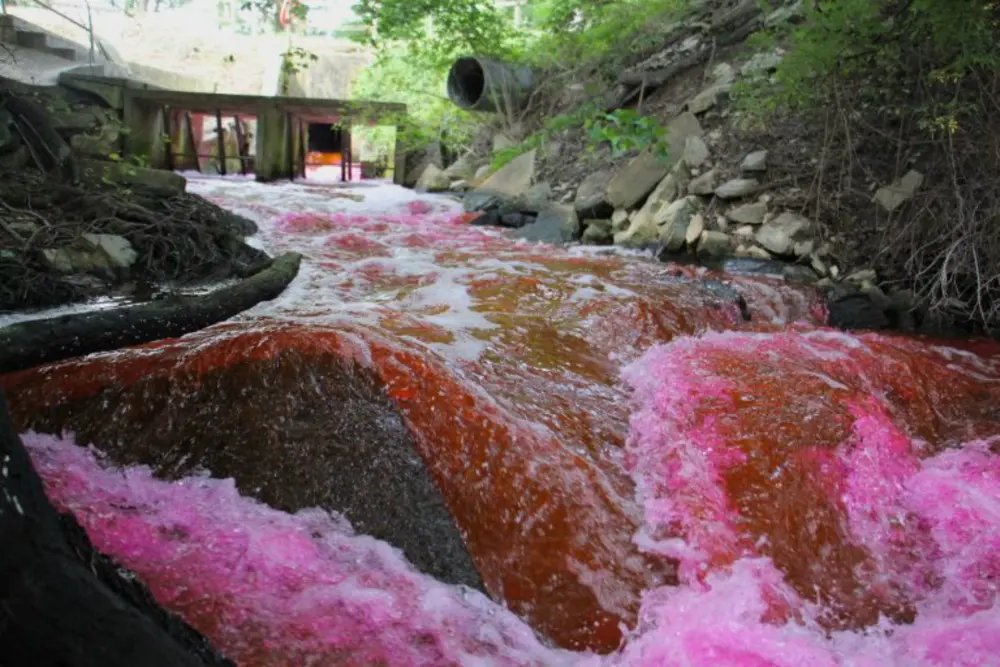

Water Contamination and Toxic Chemicals

Textile production is one of the most water-intensive and chemically hazardous industries in the world. Cotton, for example, is extremely thirsty: a single T-shirt can require 2,700 liters of water to produce — the amount one person drinks in two and a half years.

But the most severe water impacts come from dyeing and finishing processes. Factories often dump untreated wastewater, laden with toxic dyes, heavy metals, and finishing chemicals, directly into rivers. The result: entire waterways running red, blue, or black depending on the season’s palette. These pollutants not only devastate aquatic ecosystems but also poison the drinking water of communities living downstream.

Textile dyeing is responsible for 20% of global industrial water pollution.

Beyond environmental damage, there are human health costs: people exposed to contaminated water suffer higher rates of skin conditions, cancers, and respiratory illnesses.

Leather production is another major culprit. Human Rights Watch has documented tannery workers exposed daily to hazardous chemicals like chromium, with little to no protective equipment. In Bangladesh’s Hazaribagh district, workers have developed chronic illnesses while nearby residents face toxic air and water.

Deforestation and Land Use

Fashion’s appetite for raw materials drives large-scale deforestation and land-use change. Rayon and viscose production, for instance, consumes millions of trees each year. In some cases, these come from ancient and endangered forests. Converting these forests into pulp plantations not only destroys critical habitats for wildlife but also releases vast stores of carbon.

Animal-derived materials also carry enormous ecological costs. Leather, wool, and cashmere link fashion directly to livestock farming, one of the world’s largest sources of methane — a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term.

Methane emissions are a significant but largely overlooked environmental threat for fashion.

This is not just a climate issue but a biodiversity crisis. Grazing livestock for wool and cashmere degrades fragile grasslands, contributing to desertification in regions like Mongolia. Meanwhile, leather demand contributes to cattle-driven deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

Greenhouse Gases and Overproduction

The fashion industry contributes more emissions than international shipping and aviation combined. From growing cotton and producing polyester, to transporting goods worldwide and powering factories, fashion’s carbon footprint is enormous. The United Nations has estimated the sector is responsible for about 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

But the biggest issue isn’t just how clothes are made — it’s how many are made. Global clothing production has doubled in the past 15 years, yet the average garment is worn fewer times before being discarded. Even if a shirt is made from organic cotton or recycled polyester, if it’s only worn twice, its environmental footprint per use is enormous.

Overproduction is at the core of fashion’s climate problem. As long as business models depend on flooding the market with cheap clothing or overstocked collections, emissions will continue to rise.

Worker Exploitation and Unsafe Conditions

Fashion’s human toll is just as grave as its environmental one. Low-wage workers, often women in developing countries, produce the majority of the world’s clothing under harsh conditions.

The 2013 Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh was a brutal reminder of these realities. “Over 1,100 people — mostly garment workers — lost their lives when the Rana Plaza factory collapsed” (ILO, 2023). The tragedy highlighted unsafe buildings, excessive hours, and a lack of accountability from the global brands that sourced from those factories. These human costs underpin the low prices of cheap clothing.

We are not asking for charity—we are asking for the right to live with dignity.

Since then, some safety improvements have been made, but exploitation remains widespread. Many garment workers earn poverty wages, working 12–14 hour shifts in unsafe environments. In textile and leather processing, workers are routinely exposed to toxic chemicals, developing chronic health problems with little medical support.

Animal Cruelty

Animals are another hidden casualty of fashion. Fur farming often involves keeping animals in cramped cages before inhumane slaughter. Investigations into angora and mohair production have revealed animals screaming in pain as their fur is ripped or sheared. Exotic-skin industries — producing handbags, belts, and shoes from crocodile or snake skins — often involve cruel practices such as live-plucking or caging animals in inhumane conditions.

Even mainstream leather production lacks consistent welfare standards. Most leather comes as a by-product of the meat industry, but demand for hides contributes to intensive livestock farming and deforestation. For consumers who assume luxury goods imply ethical sourcing, the reality can be sobering.

Animals are not ours to wear.

Other Hidden Harms

Fashion’s footprint extends even further:

• Microplastics: Billions of microfibers shed from synthetic garments during washing have been detected in oceans, soils, and even human bodies.

• Greenwashing: Many “eco” lines exaggerate sustainability claims, offering recycled materials or token initiatives while overall production keeps rising.

• Burning waste: Unsold garments are often incinerated, wasting resources and releasing harmful emissions.

These issues highlight a pattern: even well-intentioned solutions can be undermined if production and consumption keep accelerating.

What Can Be Done?

The fashion system is vast, but it is not immutable. Change requires both systemic reform within the industry and shifts in consumer behavior.

Industry Solutions

Circular design: Produce garments to last, be repaired, and eventually recycled.

Transparency: Disclose supply chains and labor practices.

Safer production: Mandate wastewater treatment and ban hazardous chemicals.

Fair labor: Ensure living wages, safe workplaces, and rights to organize.

Reduce overproduction: Move away from endless growth toward measured, sustainable output.

Consumer Actions

Buy less, buy better: Choose durable, high-quality garments or secondhand clothing.

Extend garment life: Wash less, repair damages, repurpose old items.

Support ethical brands: Look for transparency and verified certifications.

Advocate for policy: Push for extended producer responsibility, stronger labor protections, and environmental regulations.

Conclusion

Fashion’s glossy image hides a much darker reality: polluted rivers, poisoned workers, deforested landscapes, and billions of discarded garments choking our landfills. From fast fashion to high-end luxury, the industry leaves few parts of the planet untouched.

Yet change is possible. As UNEP and other experts stress, the industry has the knowledge and tools to reduce its footprint — but it will take consumer pressure, government regulation, and corporate accountability to make it happen. By buying less, demanding transparency, and supporting systemic reforms, we can turn fashion from one of the world’s most destructive industries into a force for sustainability and fairness.

True style should never come at the expense of people, animals, or the planet.

References

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2018). Textiles: Material-Specific Data. “Landfills received 11.3 million tons of MSW textiles in 2018.”

United Nations Environment Programme (2020). The environmental costs of fast fashion.

Vox (2018). Why fashion brands destroy millions worth of their own merchandise.

International Labour Organization (2023). The Rana Plaza disaster ten years on: What has changed.

Human Rights Watch (2012). Toxic Tanneries: The Health Repercussions of Bangladesh’s Hazaribagh Leather.

Changing Markets Foundation (2017). Dirty Fashion: How pollution in the global viscose supply chain is making textiles toxic.

Collective Fashion Justice, NYU, Cornell (2024). Methane emissions analysis. “Methane emissions are a significant but largely overlooked environmental threat for fashion.”

European Environment Agency (2020). Microplastics from textiles: towards a circular economy for textiles in Europe.

Siegle, Lucy. To Die For: Is Fashion Wearing Out the World? Fourth Estate, 2011.

Quotes: Stella McCartney (2017), Jane Goodall (2002), Kalpona Akter (2019).